Anatomy of the Lingual Nerve

The lingual nerve is a branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve supplying the anterior two thirds of the tongue and responding to stimuli of pressure, touch, and temperature (Image #1 & 2).

Image #1 : Tongue Anatomy

Image #2: Lingual Nerve Innervation

There is a lingual nerve for the right side of the tongue and one for the left side. The lingual nerve also carries a branch of the facial nerve called the chorda tympani which splits off the lingual nerve before the tongue is innervated and provides the sensation of taste to the anterior (front) two-thirds of the tongue. The mandibular nerve (V3) is the largest of the three branches of the trigeminal nerve. We are interested in the posterior division of the mandibular nerve which separates into the lingual nerve and the inferior alveolar nerve (Image #3). The lingual nerve runs to the medial (inside of the mandible or lower jaw) and next to the inferior alveolar nerve (Image #2) as they move towards the ramus of the mandible.

Image #3: Mandibular Nerve with the lingual nerve and the inferior alveolar nerve

The lingual nerve takes the inside track next to the mandible and runs next to the third molar (wisdom tooth or teeth No. 17 on the left and No. 32 on the right -Image #3) on the lingual side (tongue side) of the third molar(Image #5).

Image #4: Path of the lingual nerve which tracks to the inside of the mandible (lower jaw)

There is a boney barrier between the third molar and the lingual nerve called the lingual plate (Image #5) which the lingual nerve runs along on the lingual side (tongue side).

Image #5: Lingual nerve in relation to the lingual plate and third molar

After passing the third molar, the lingual nerve runs below tongue, sending nerve branches up to the anterior (front) two thirds of the tongue (See Image #2) above which demonstrates the area of the tongue which the lingual nerve innervates in blue).The lingual nerve also carries nerve fibers that are not part of the trigeminal nerve, including the chorda tympani nerve (a branch of the facial nerve or cranial nerve VII), which provides special sensation (taste) to the anterior 2/3 part of the tongue. It is also important to keep in mind the inferior alveolar bundle in relationship to the third molar which can also be injured during the third molar extraction (See Inferior alveolar nerve damage following removal of mandibular third molar teeth. A true close relationship between the third molars and the mandibular canal increases the risk of injury to the inferior alveolar nerve, and an accurate evaluation of the relationship is essential to avoid the risk of surgery. Dentists should be aware of the limitations of the radiographic markers of panoramic radiography and should consider the more detailed imaging of CBCT in specific cases in which the radiographic findings raise concerns of potential injury to the inferior alveolar nerve due to the close relationship between the third molar and the mandibular canal.

Dental Malpractice and the Lingual Nerve

The vast majority of lingual nerve injuries occur during the extraction of a mandibular third molar (lower wisdom tooth) by damage or removal of the lingual plate, or by retraction of the soft tissue, including the lingual nerve, in obtaining access to the mandibular third molar. (See Image #5 above). Damage to the inferior alveolar nerve is discussed later. Although it is likely that you signed an informed consent for the extraction of your wisdom tooth that says one of the inherent risks of a third molar extraction is damage to the lingual nerve, this informed consent is usually nothing more than a proactive measure to convince the patient that his/her injury was just one of those things. The written informed consent does not absolve the dentist from a negligent extraction that causes nerve injury. If there is a complete loss of feeling in the anterior two thirds of the tongue, then this is called complete anesthesia (numbness). If parts of the tongue are numb, but there are abnormal sensations of the tongue, such as tingling, burning, pricking or creeping on the tongue, we call this paresthesia. The word dysesthesia is used to describe an abnormal sensation that is considered to be unpleasant (paresthesia is sometimes used to be inclusive of dysesthesia). If there is complete numbness, then there is no nerve signal getting through from the tongue to the brain and if there is no change in the patient's condition over time, then it is likely that the lingual nerve has been severed. If there is some feeling or paresthesia/dysesthesia, then some signal is getting through the injured area of the lingual nerve and some improvement may occur over time. You can find additional information concerning dental pain and neuropathic pain management from the International Association For The Study Of Pain.

The Negligent Dentist and the Platiff's Burden of Proof

Proving that dental malpractice occurred in the extraction of a third molar can be difficult. In a dental malpractice case, the burden of proof is upon the plaintiff/injured party to prove the dentist was negligent during the extraction of the third molar and that this is the cause of plaintiff's lingual nerve injury. The dentist may also have been negligent in the post-operative care of the patient which has resulted in nerve injury or failure to resolve or minimize same. It is generally easier to prove negligence when it is a general dentist who injures the lingual nerve during a third molar extraction due to the disparity in their training when compared to an oral surgeon. The issues of proof for both the general dentist and the oral surgeon will be influenced by the nature of the injury i.e. anesthesia, paresthesia/dysesthesia. Here are some of the considerations to determine if there is a basis for a claim against a dentist for the negligent extraction of a third molar:

a. Is there a signed written consent form listing the risks of nerve damage;

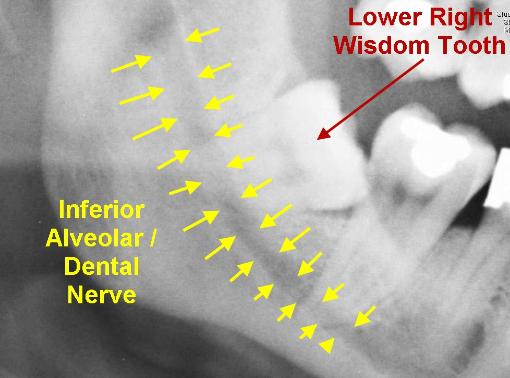

b. Are there adequate x-ray studies of the third molar before extraction. The radiograph should show complete visualization of the third molar and surrounding anatomical landmarks(see Image below; see also, the page on Cone Beam CT or CBCT below);

Image #6a: Panoramic x-ray of the third molar in relation to the inferior alveolar nerve

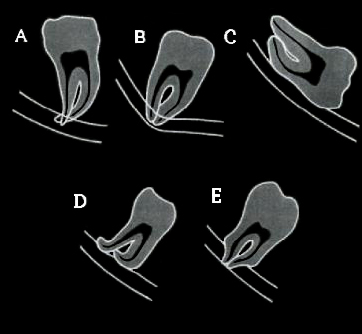

c. Was this a high risk extraction that should have been referred by the general dentist to an oral surgeon. Is the third molar fully erupted, partially erupted or fully impacted. What is the position of the tooth and where is in located in relationship to anatomical landmarks, namely the relationship of the roots to the inferior alveolar nerve canal, or overlapping that canal on radiographs. If there is doubt as to the position of the third molar in relationship to the inferior alveolar canal on standard screening with periapical and panoramic x-rays, then a Cone Beam CT (CBCT) radiographic examination should be requested by the dentist before extraction of the third molar (See Image 6a above and Image 6b below);

Image 6b: Five radiographic signs indicating juxtaposition of the mandibular canal to the third molar roots, as described by Rood and Shelab 1990. Signs significantly related to nerve injury are: A. Radiolucency across the roots of the third molar; B. Deviation of the mandibular canal; C. Interruption of the white lines of the canal. Signs considered to be clinically important: D. Deflection of the third molar roots by the canal; E. Narrowing of the third molar root.

d. Was improper technique or too much force used, resulting in a fracture of the lingual plate or over retraction of the soft tissue overlapping the lingual plate and instrumentation of the lingual nerve;

e. A written report or notes on the extraction surgery should exist in the patient's dental record, but it is not uncommon that this written record does not reflect all of the difficulties that the dentist encountered during the extraction. The actual length of time that the extraction actually took may be an indicator that the dentist had more difficulty with the extraction than his records reflect. Most oral surgeons can extract a third molar in fifteen (15) minutes

f. Did the dentist properly treat the acute nerve inflammation post-operatively andfollow the healing of the nerve injury or lack thereof with nerve mapping to determine if there is any improvement in the nature and/or distribution of the patient's symptoms (See Image 6c below). Sometimes the territory of numbness or neuropathic pain becomes smaller over time and if it does not; the dentist may be required to make appropriate referrals;

Image 6c: Nerve mapping of an injury to the inferior alveolar nerve

g. Did the general dentist/oral surgeon timely refer the patient to an oral-facial pain specialist to treat the patient's neuropathic pain before the problem became worse? Did the dentist refer the patient to an oral surgeon trained in micro-surgery to timely present the patient with the options of nerve decompression microsurgery (removing a hematoma, scar tissue or anything that impinges on the nerve). See Retrospective Review of Microsurgical Repair of 222 Lingual Nerve Injuries, from the Journal of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery 2010;

h. Does a subsequent Cone Beam CT (CBCT)indirectly confirm the location and nature of the lingual nerve injury. If the CBCT demonstrates that the lingual plate has been violated or if exploratory surgery by a micro-surgeon directly visualizes complete transection of the lingual nerve, many of the defenses for the treating dentist are eliminated; and

i. Is there evidence that the papillae on the tongue surface have atrophied. If so, this isevidence that the papillae are not being innervated (injury to the lingual nerve or the chorda tympani).

Defense Arguments

The defense will argue the following:

-

the lingual nerve was injured during the administration of the local anesthetic for the extraction of the third molar (mandibular block) and not the extraction and that this is an unavoidable risk of a mandibular block . This argument is a more effective argument in cases of paresthesia (incomplete severing of the lingual nerve), than with complete anesthesia (complete severance of the lingual nerve), given the width of the bevel tipped syringe needle and the width of the nerve at the location of the mandibular block;

-

the general dentist is experienced in performing extractions and there was no need to refer the plaintiff to an oral surgeon or alternatively, the dentist did refer the plaintiff to an oral surgeon (but failed to record this fact in the dental records), but plaintiff chose not to spend the extra money for the oral surgeon to extract the tooth;

-

the plaintiff signed a written consent acknowledging the risks of nerve injury, etc. If there is no written consent, the defense will argue that plaintiff was orally informed of the risk, whether the dental chart confirms this or not;

-

the dentist performed an excellent textbook extraction, using appropriate technique for the subject third molar. Bad things just happen;

-

the subject extraction appeared from the diagnostic workup by the treating dentist to be an uncomplicated extraction;

-

the plaintiff has an incomplete injury to the lingual nerve and the symptoms of anesthesia, paresthesia, dysesthesia will resolve in time (certainly after the jury verdict). When there has been no change in the patient's anesthesia, paresthesia, dysesthesia after 1 year, the defense expert who claims that it is probable that the patient's symptoms will resolve after the jury verdict, or continue to improve is taking a position that is not supportable in the dental literature.